The Indian media is engrossed in events taking place in neighboring Bangladesh — and understandably so. The 15-year rule of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina came to an end on Monday with her resignation as student protesters converged near her residence.

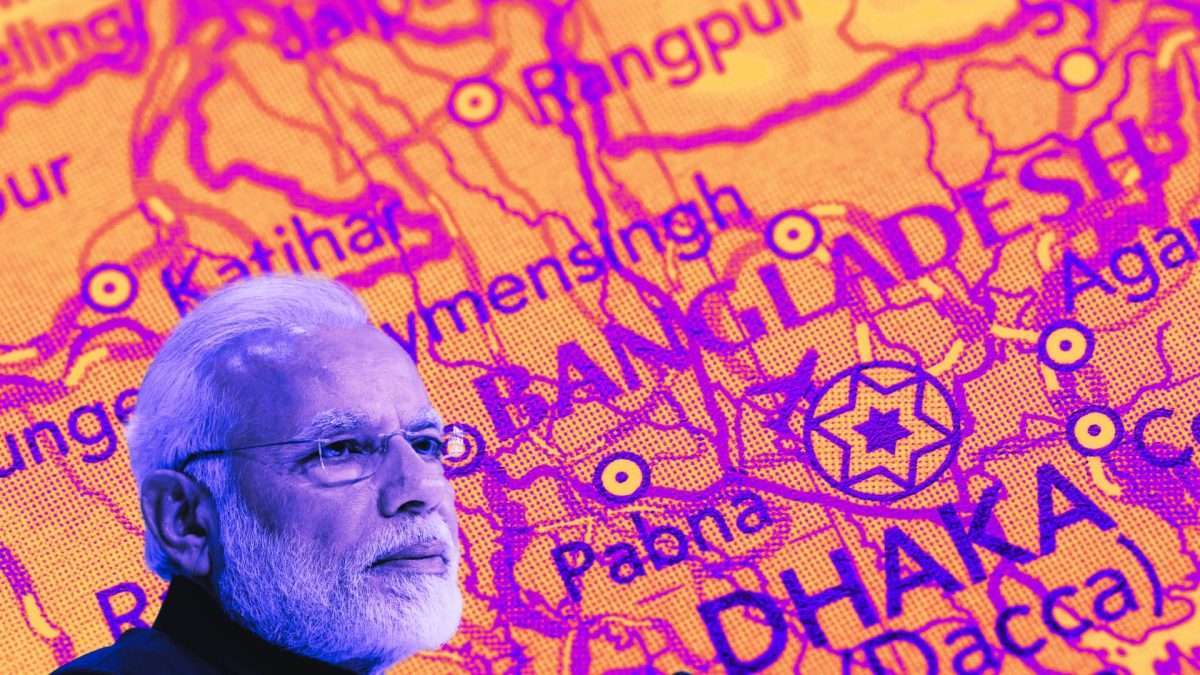

For India, the fall of Hasina and the apparent end to her political career is the loss of not just a long-time ally, but also its most reliable partner in South Asia. In Bangladesh, a country of 170 million people, India put all its eggs in the Hasina basket, which has now fallen apart.

This is the latest in a series of setbacks for India in the region. India’s tenuous influence in its near-periphery is the result of a foreign policy driven by arrogance and ideology, combined with relatively limited practical capabilities. And it should give pause to declarations of its emergence as a global power.

India’s Long Affair With Hasina

India has a complicated history with Bangladesh. Ethnic Bengali Muslims supported the creation of Pakistan as a Muslim homeland out of parts of British India — including Muslim-majority regions of Bengal. Relations between the two wings of Pakistan — a multiethnic West Pakistan dominated by the army and feudal politicians, and a mainly Bengali East Pakistan — grew estranged over the decades and erupted into a calamitous civil war in 1971. India provided support to Hasina’s father, Sheikh Mujib-ur-Rahman, and his movement to separate from Pakistan. They succeeded — and Bangladesh became independent that year.

But not all Bangladeshis, especially those on the right and in the army, shared Hasina’s affinity for India. Many saw India also as a bully regarding water sharing and other bilateral issues.

Bangladeshis have soured on India over the past decade, as its Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party incited violence against Muslims, including fellow ethnic Bengalis, who have been labeled as “infiltrators.” India has also doubled down on its alliance with Hasina as her rule became increasingly authoritarian and kleptocratic, imprisoning and, in some cases, executing, members of the opposition. It even asked the Biden administration to go soft on her.

New Delhi’s Bangladesh policy in effect became a Hasina policy. Hasina is now gone. And in the driver’s seat in Dhaka, outside of the army, are her victims.

The Paranoid Style in Indian Foreign Policy

The collapse of Hasina’s regime has shaken New Delhi. But rather than looking within, prominent Indian commentators are instead blaming foreign hands. Leading Indian news outlets allege Chinese, Pakistani, and even American hands in the fall of Hasina. Some have even suggested that Hasina was ousted by a joint Sino-American-Pakistan regime change operation.

Amusingly, as the hypernationalist Republic news channel interviewed Sheikh Hasina’s son, Sajeeb Joy Wazed, it claimed that the prime minister was brought down by the American “deep state.” Ironically, Wazed lives in Great Falls, Virginia — just a twenty-minute drive from the Central Intelligence Agency headquarters.

The deluded, paranoid commentary from New Delhi on the political change in Dhaka is a hallmark behavior of a sore loser. It comes not just from crackpot commentators, but also recently retired senior diplomats who have worked closely with Washington, reflecting a paranoid style in Indian foreign policy and a distrust of the United States and other Western powers that endures despite being feted by the West as a counterweight to China.

Flexibility Globally, Hardline Closer to Home

Globally, India has been deft in making the most of this multipolar era. It maintains strong ties to Russia even as it draws closer to the West. It’s sat on the sidelines in the Russia-Ukraine war, dismissing the conflict as a European one. Simply put, it has had its cake and eaten it too. New Delhi calls this “strategic autonomy” — a rebranded version of its Cold War “non-alignment.”

But closer to home, Indian foreign policy hasn’t been as nimble. India has picked favorites and sought to impose its will on its smaller neighbors, even going so far as to blockade Nepal, which, along with Sri Lanka, has grown relations with China.

India’s strategic arrogance in South Asia is partly the result of domestic politics. Hindu nationalists promote the idea of Indian — and more specifically, Hindu — hegemony in the broader region. A revisionist, irredentism remains part of the Hindutva ideology. Many Hindu nationalists believe most if not all of the region from Afghanistan to Myanmar should be theirs. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has also cultivated a strongman image — that he can engage in unilateral, kinetic actions in neighboring states.

India’s haughtiness has also been enabled by Washington, where successive administrations have described New Delhi as a “net security provider” in the region, and the disarray its sole South Asia competitor, Pakistan, finds itself in.

But as India’s predicament in Bangladesh shows, its regional obduracy is not without costs. China is a major provider of arms and development financing in South Asia. It has become a peer of India in South Asia itself, partly driven by the momentum of its state capitalism, but also by the desire of regional states for a counterweight to India.

India is on the back foot in South Asia due to its bad bets, not imaginary conspiracies.

Arif Rafiq is the editor of Globely News. Rafiq has contributed commentary and analysis on global issues for publications such as Foreign Affairs, Foreign Policy, the New Republic, the New York Times, and POLITICO Magazine.

He has appeared on numerous broadcast outlets, including Al Jazeera English, the BBC World Service, CNN International, and National Public Radio.